In my Western Civilization course, students and I discuss the biblical books of Genesis, Job, and Mark in several meetings of the course. We do this in order to examine what life was like living in the Ancient Near East and in an occupied area of the Roman Empire. We also discuss the scriptures to analyze the theological contributions that have influenced the western world. Discussing the Bible as literature and with a critical eye to mostly traditional Judeo-Christian students is not always easy. Most students do not know that in the first couple of chapters in Genesis there are two creation stories with two distinct messages. Other students are appalled when I tell them that within ancient monotheism, as illustrated in the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible, the concept of a devil was not invented yet. Instead, evil was perceived to be the result of people’s immoral decisions and not demonic influences. They then are really displeased when I note that the Hebrew Bible does not have a single authorship but perhaps was written by a variety of writers over centuries and who all had different perspectives and agendas.

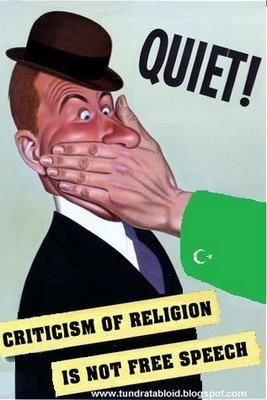

These ideas remain shocking to students when we shift over to the Gospel of Mark. There we discuss the the resurrection account and how it was not in the original gospel but would be added much later. We also discuss the fact that the other three gospels used the Gospel of Mark as a source when creating their accounts. These conclusions are not ones made up by me to trick students. Rather they are the result of years of biblical scholarship and literary analysis. As a professor having these discussions with students, challenging prevailing ideologies, getting my students to see inconsistencies, and debunking the belief that the ancient writers were that interested in what we modern readers are obsessed with (ie. science and accuracy), I get several accusations thrown my way. The most popular one is that I must be an atheist. I recently received an email from a student in which they accused me of being a teacher who “slam(s) Christianity and (present an) over glorification of other beliefs”. Most of my students are surprised at the end of the semester when I reveal to them that I am a Christian. Moreover, I am a Christian who is also an ordained minister and has been for ten years. I am also a budding philosopher who is a free and critical thinker. I am very comfortable and secure with critically looking at scripture and with breaking the “Thou Shall Not Critique Religion” commandment that some religious people unfortunately hold on to as a defense against attacks to their faith.

The resistance and the comments reveal a prevailing misconception that any questioning of the sacred, any critique of accepted beliefs, and any challenge to authority are either acts of disrespect and blasphemy or the usually practice of unbelievers. As an educator I want my students to think critically, even if its about something that is dear to them. Critical thinking skills provide them with the tools needed to help them retain their autonomy and to live lives as citizens rather than robots within social systems. The freedom to critique also allows people to find truth. This is what I want for my students and for the world. This is my vocation and also my ultimate challenge. I will remain consistent and fearless.

What people often forget is that it was the breaking of the commandment of “Thou Shall Not Critique Religion” that helped create the movements and transformations that my students are blessed to benefit from today. The Protestant Reformation, Abolitionist Movement, and Civil Rights Movement came out of biblical and religious critique. It is my hope that this critique will also soon aid in obtaining rights for immigrants, the LGBT community, and other oppressed groups. Therefore, I welcome anyone I come in contact with to break this commandment as logically and passionately as they can.

There are a couple of articles this week that speaks about this issue of religion, critique, and protest. David Brooks has an article in the New York Times where he discusses the “Love Jesus, Hate Religion” video and gives some advice to students about How to Fight the Man . Stephanie Pappas reveals in LiveScience that Low IQ’s and Conservative Beliefs May be Linked to Prejudice. I think this scientific finding connects to the religious critique discussion because what the reading suggest is that lower cognitive ability leads to simple ways of thinking about the world. This inability to think rigorously may lead people to be comfortable with what they already think they know and believe without a desire and openness to think differently. They in turn put up a defense when presented with information that goes against those beliefs they already have. In the Room for Debate section of the New York Times, my good friend Josef Sorett presents discussions around Black Churches and a New Generation of Protest . In the debate section are some interesting reads such as “The Prosperity Gospel versus the King legacy” by Fredrick Harris and “Class, Sexuality, and Lessons Unlearned” by Josef Sorett. Each of these articles were written by intellectuals who are also people of faith. It is because of their faith not the absence of it that they are dedicated to challenging the status quo, irrational thinking, and resistance to change.

The greatest trick the devil pulled was not convincing people that he didn’t exist; the devil’s greatest trick was convincing people to not think for themselves.

Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom: and with all your getting get understanding. -Proverbs 4:7